“Thank God that’s not the test of whether or not people have rights in this country or not, whether or not they pass your look test.” That’s what then-Rep. George Miller (D) said to Donald Trump when the latter was railing against “so-called Indians” before  Congress. “You’re saying only Indians can have the reservations, only Indians can have the gaming, so why don’t you approve it for everybody?”, Trump asked. Now he is in the White House, his Secretary of the Interior has taken land out of trust for the first time since the Termination Era (1946-1975) and the Mashpee Wampanoag find themselves outside looking in. The Termination Act was a bit of Harry Truman administration policy to try and force Native Americans to assimilate by dissolving their reservations. As erstwhile Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell (R) put it, “If you can’t change them, absorb them until they simply disappear into the mainstream culture … In Washington’s infinite wisdom, it was decided that tribes should no longer be tribes, never mind that they had been tribes for thousands of years.”

Congress. “You’re saying only Indians can have the reservations, only Indians can have the gaming, so why don’t you approve it for everybody?”, Trump asked. Now he is in the White House, his Secretary of the Interior has taken land out of trust for the first time since the Termination Era (1946-1975) and the Mashpee Wampanoag find themselves outside looking in. The Termination Act was a bit of Harry Truman administration policy to try and force Native Americans to assimilate by dissolving their reservations. As erstwhile Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell (R) put it, “If you can’t change them, absorb them until they simply disappear into the mainstream culture … In Washington’s infinite wisdom, it was decided that tribes should no longer be tribes, never mind that they had been tribes for thousands of years.”

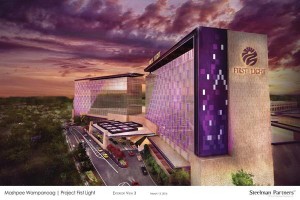

Ominously, the Trump Interior Department has dropped the appeal of a lawsuit that went against the Wampanoag, endangering their Project First Light casino in Massachusetts (and now the Massachusetts Gaming Commission may open southeastern Massachusetts to private-sector competition).  Despite being led astray by “Casino Jack” Abramaoff, the Mashpee eventually achieved federal recognition and were awarded 321 acres of land by the Obama administration. (We’re drastically collapsing tribal history here, folks.) Although 60% of Taunton favors First Light, spoilsports David and Michelle Littlefield have sued the Mashpee on the grounds of “reservation shopping,” citing failed land acquisitions in two other towns.

Despite being led astray by “Casino Jack” Abramaoff, the Mashpee eventually achieved federal recognition and were awarded 321 acres of land by the Obama administration. (We’re drastically collapsing tribal history here, folks.) Although 60% of Taunton favors First Light, spoilsports David and Michelle Littlefield have sued the Mashpee on the grounds of “reservation shopping,” citing failed land acquisitions in two other towns.

The Littlefields are not exactly disinterested observers. Their court case is being bankrolled by Neil Bluhm, who wants to build a casino in nearby Brockton. That puts “george” Democratic Party donor Bluhm on the same side as Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. The irony is so thick you could slice it. Then throw in a bunch of troglodytes who call themselves the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance and for whom Native American self-governance is “unconstitutional … racist.” Whoever said irony died on 9/11 never spent any time around Indian Country.

The courts continue to uphold Carcieri v. Salazar, which ruled that tribes not recognized before 1934 cannot have land taken into trust. The Obama administration argued that the Wampanoag “need only be ‘recognized’ at the time the statute is applied (e.g., at  the time the Secretary decides to take land into trust).” Replied the court, “With respect, this is not a close call.” Trump administration Bureau of Indian Affairs chief James Cason set a June 2017 deadline for proponents and opponents of First Light to make their cases. Evidently Cason couldn’t wait to make a decision, turning the Mashpee down on the day of the deadline. A week later, Cason sidestepped his original decision, calling for further review. Perhaps, he suggested, Massachusetts could act as “a surrogate for federal jurisdiction.”

the time the Secretary decides to take land into trust).” Replied the court, “With respect, this is not a close call.” Trump administration Bureau of Indian Affairs chief James Cason set a June 2017 deadline for proponents and opponents of First Light to make their cases. Evidently Cason couldn’t wait to make a decision, turning the Mashpee down on the day of the deadline. A week later, Cason sidestepped his original decision, calling for further review. Perhaps, he suggested, Massachusetts could act as “a surrogate for federal jurisdiction.”

“Interior has now looked under that rock, knows nothing is there, but refuses to say so, proving how reluctant it is to turn down a tribe’s land-into-trust application even when required by law,”  screeched the plaintiffs. “The fact that Interior raised this unprecedented, never-before-articulated and implausible theory at the eleventh hour says much about its validity.” The filing also included the assertion that Genting Group had “all but written off” the $475 million to which it had grubstaked the Mashpee and quoted Cason as confessing he “has a hard time saying ‘no’ to tribes.”

screeched the plaintiffs. “The fact that Interior raised this unprecedented, never-before-articulated and implausible theory at the eleventh hour says much about its validity.” The filing also included the assertion that Genting Group had “all but written off” the $475 million to which it had grubstaked the Mashpee and quoted Cason as confessing he “has a hard time saying ‘no’ to tribes.”

For Cason’s part, his attorneys responded, “Plaintiffs … already have all the relief they need. The [tribe] has been unable to move forward with its planned gaming establishment.” Interior, meanwhile, is fiddling with a possible reform of its time-consuming land-into-trust process. Buried at the bottom of the document is a kicker saying that if land has been taken into trust and the courts rule that the department “has erred,” it reserves the right to  take the land back out of trust again, a reversal of Obama-administration policy. This should cause some serious disquiet among those 14 other tribes who are seeking to regain federal recognition. As the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians of Louisiana wrote to the House of Representatives, “Every federally recognized tribe in the United States is entitled to a federally protected reservation where it can exercise its sovereignty, protect its culture and benefit from the federal laws and programs that are tied to having reservation land.”

take the land back out of trust again, a reversal of Obama-administration policy. This should cause some serious disquiet among those 14 other tribes who are seeking to regain federal recognition. As the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians of Louisiana wrote to the House of Representatives, “Every federally recognized tribe in the United States is entitled to a federally protected reservation where it can exercise its sovereignty, protect its culture and benefit from the federal laws and programs that are tied to having reservation land.”

On September 27, the Mashpee came off the sidelines and announced their intention they were “challenging the U.S. Department of the Interior’s most recent failure to take action to  preserve and protect the Tribe’s reservation as arbitrary, capricious, and contrary to the Department’s own administrative decisions and clear law.” Tribal Chairman Cedric Cromwell added, “I do not believe that our country, this great nation that our Tribal citizens have fought and died for, wants to return to the dark days of taking sovereign Indian land away from indigenous communities.” In addition to filing suit, the tribe also ramped up the pressure on Congress to pass Sen. Elizabeth Warren‘s Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe Reservation Reaffirmation Act.

preserve and protect the Tribe’s reservation as arbitrary, capricious, and contrary to the Department’s own administrative decisions and clear law.” Tribal Chairman Cedric Cromwell added, “I do not believe that our country, this great nation that our Tribal citizens have fought and died for, wants to return to the dark days of taking sovereign Indian land away from indigenous communities.” In addition to filing suit, the tribe also ramped up the pressure on Congress to pass Sen. Elizabeth Warren‘s Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe Reservation Reaffirmation Act.

The tribe is suing Zinke directly, accusing him of “contorting some of the relevant facts and ignoring others to engineer a negative decision.” The case hinges, first and foremost on whether the tribe was ‘under federal jurisdiction’ post-1934, the penumbra under which most Carcieri v. Salazar-related cased take refuge. “Secretary Zinke is responsible for the arbitrary, capricious, and unlawful conduct described in this Complaint.” The  tribe’s arguments are somewhat esoteric and difficult to summarize for S&G purposes but suffice it to say that the lawsuit stands or falls on whether the Mashpee can demonstrate a relationship with the federal government predating the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The tribe has marshaled a long list of arguments (sample toe-tapper: “The Department acknowledged that in 1798, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts brought an ejectment action on behalf of the Mashpee Tribe and successfully invalidated an illegal conveyance of tribal land in Mashpee, contrary to an existing restraint on the alienation of that Indian land”) as to why this is so but, as we have seen, the courts have set a high bar for the Mashpee to clear.

tribe’s arguments are somewhat esoteric and difficult to summarize for S&G purposes but suffice it to say that the lawsuit stands or falls on whether the Mashpee can demonstrate a relationship with the federal government predating the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The tribe has marshaled a long list of arguments (sample toe-tapper: “The Department acknowledged that in 1798, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts brought an ejectment action on behalf of the Mashpee Tribe and successfully invalidated an illegal conveyance of tribal land in Mashpee, contrary to an existing restraint on the alienation of that Indian land”) as to why this is so but, as we have seen, the courts have set a high bar for the Mashpee to clear.

Zinke will probably take refuge in the argument that the government merely gave “acknowledgement” of the Mashpee, not full recognition. The tribe will respond that the department’s handling of the matter has been “arbitrary, capricious, and contrary to law.” The tribe seeks court costs and restoration of those 321 acres to tribal control. Will it succeed? In the end the Mashpee are at the mercy of the federal bench. Rest assured, we haven’t heard the last of this story.